Commands and Contravene

When you begin a career in graphic design, one of the first things you are told are the ‘rules’ of design, followed by the condiment that is destined to happen if you break them. Why are young graphic designers being manufactured like robots with boring, interchangeable ideas that follow a textbook of ‘category‐based visual codes’ (Celhay and Trinquecoste, 2015, p.1021)? After all, there’s no excitement in graphic design if you can’t experiment. What creative mind wouldn’t want to get a buzz from letting an idea take hold of them without worrying about the consequences?

At what point in time did someone feel so imperious that they would decide on a set of design laws that each artistic mind would have to follow persistently until the end of time? In addition, these rules must have had to alter throughout the course of time to suit different audiences. For example, a German poster used to appeal to potential soldiers in world war two wouldn’t appeal to a teenage girl in the twenty first century. So how did the rules change? Was somebody brave enough to break a rule before it was deemed acceptable?

I argue that some of the most iconic and creative graphic designers smashed the rules and communicated their message in a completely unique and radical way. Daring designers have been breaking rules since the beginning of graphic design, even in the early twentieth century, in a pre-digital age. Three rule breaking designers from the beginning, middle and end of the twentieth century will be discussed throughout this essay, including the rules that they chose to violate.

But rules are meant to be broken…

Outrageous rule breaker Filippo Tommaso Marinetti grabbed the attention of the Italian media in the early twentieth century. The facilitator of madness saw the evidence of modernity shaping his world outside of sleepy Italy and demanded that he wouldn’t be left behind.

Compared to the public’s traditional views, the world looked different through Marinetti’s eyes. He believed that all things ‘ancient’ and ‘traditional’ should be destroyed to make way for the exiting new technology that the modernism movement brought to the table. A car gliding round a racetrack would be the new ballet, a telephone would be the new sculpture. The only beauty was technology, and as a wealthy man, he had the means to have it.

Ironically, Marinetti took up the traditional career as a poet. However, the work that he produced was far from the lucid rhymes that is traditionally associated with poetry. Random, aggressive and illegible, his ‘sound poems’ (see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3) distinctively threw up all traditional rules on how to write a poem in a pre-digital age. The purpose of his poems wasn’t to inform his audience of a great love affair or a breath-taking walk in the countryside but to communicate the futurist world that Marinetti was desperate to pursue. The look and feel of Marinetti’s sound poems were so futuristic for their time that the imagery could be related to the shapes that appear when creating a piece of music digitally over 100 years later (see Figure 4 and Figure 5), despite the notes that appear on parallel staffs (Lupton and Phillips, 2008, p.140) on a piece of traditional sheet music that he would have been used to.

The audience may be able to grasp an idea about the theme of a poem only from a couple of words that Marinetti purposely left legible, which brings us to the first rule. Communicate, don’t decorate - form carries meaning (Samara, 2014, p.10). The futuristic and technological movement that the ‘sound poems’ represented were very radical for their time and for the most part wouldn’t have communicated with the audience as a piece of poetry. So why are his sound poems still so well-known and inspirational today? How is Marinetti such an iconic designer if he broke the sacred rules?

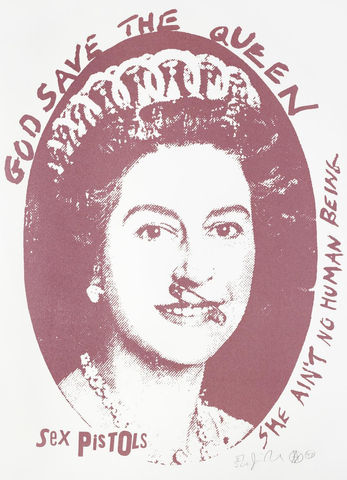

Mid twentieth century designer and rule breaker Jamie Reid caused ‘anarchy in the UK’ when he quite literally ripped up the rules when designing artwork for The Sex Pistols in the 1970’s. The Sex Pistols was an ideological as well as musical phenomenon (Faulk and Hawkins and Burns, 2010, p.134), promoted by the unforgettable artwork produced by Reid. The Dada influenced designer challenged views at the time by producing deliberately provocative artwork by manipulating and evoking symbols of the British national imagery (Faulk and Hawkins and Burns, 2010, p.133). He ripped up one of Britain’s most recognisable icons, the Union Jack, in ‘Anarchy in the UK’ (Figure 6) and defaced an image of the Queen in ‘God Save the Queen’ (Figure 7). These radical statements caused outrage throughout Britain, a country that worships it’s queen and takes pride in it’s flag and everything it stands for.

Over a decade later Reid released an unsparing piece that was designed to shock called ‘Fuck Forever’ (Figure 8). Taken directly from his understanding of the Dada art movement, the album cover shared a similar look and feel to those he designed previously due to the copy and paste technique used by influential Dada artist Hannah Hoch. He cut images out of porn magazines and placed them as the main focus of the piece, followed by the title of the album cut out letter by letter, comparable to a ransom note. There was a time that anyone caught wearing The Sex Pistols memorabilia would be arrested because of how atrocious the imagery was, bringing us to rule number two - don’t offend your audience. This rule is understandable for the most part, but like Marinetti, Jamie Reid deliberately offended his audience with his work in order to get a lot of attention from the media which successfully lead The Sex Pistols to their fame. Reid was not only a rule breaker in design, but in the law. Why is such a villainous designer so widely celebrated today?

Following in Reid’s unscrupulous footsteps, typography designer David Carson broke many rules with his designs in the late twentieth century and the twenty first century, creating pieces that were for the most part unreadable, much like Marinetti (see Figure 9 and Figure 10). A deep fascination about how an audience can get a message from a piece of work before they’ve even read it has led to a considerable number of designs that will continue to be analysed for many years to come.

Some may argue that because Carson didn’t spend long training as a designer, he couldn’t have understood the rules. However, I argue that he did because no matter if you want to follow the rules or you want to break them, you have to know them first and know them well (Adams and Dawson and Foster and Seddon, 2012, p.10), which is what made his designs so phenomenal when he broke them. His work most recognisably breaks rule number three – text must be legible. The theory behind this rule is that if the audience cannot read the text, they will be unable to identify the meaning of the design, therefore making the piece unsuccessful. On the contrary, Carson quotes “don't confuse legibility with communication”, explaining that a design doesn’t communicate just because its legible (TED, 2019). A designer that can communicate their message without any text at all is the best designer there is.

Design is always influenced by individual preferences (Min Soo Chun and Brisson, 2015, p.9) which is clear to see in Carson’s work. You can see his personality shining through when you gaze at his vast collection of masterpieces, particularly when analysing his range of Quiksilver poster designs. Being a surfer himself, Carson was well suited to the surf wear brand and he was given the freedom to put his own stamp on the designs. The 2011 pro France poster (Figure 11) in particular is a very interesting piece of work, from the mixed media that can be related to Jamie Reid’s God Save the Queen (Figure 7) to the typography which breaks the fourth rule - use two typeface families, maximum (Samara, 2014, p.10).

When discussing breaking convention, Carson is one of the most successful and familiar graphic designers throughout the world. He has designed pieces for many big companies including Pepsi, Ray Ban, Nike and Microsoft, all great achievements for a graphic designer and something that an unsuccessful designer wouldn’t be able to achieve. So why would such a scandalous rule breaker be such a popular choice for so many reputable brands?

Four graphic design rules have been outlined throughout this essay. These are just a few rules from the list that are taught to hopeful designers at the beginning of their career. Ignoring the catalogue of rules, the three rule breakers from throughout the twentieth century each have their own distinctive style, breaking the rules in their own unique way in order to let their creativity flow, resulting in a number of unforgettable designs. I have questioned the commands, established that to break the rules you must first understand them and explored three different famous graphic designers that gained their success from breaking them and the answer to my questions is this – the designs that refuse to conform to the rules have been so successful because rules are meant to be broken.

Bibliography

Min Soo Chun, A and Brisson, I E. (2015) Ground Rules in Humanitarian Design: AD Reader. 1st ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Adams, S and Dawson, P and Foster, J and Seddon, T. (2012) Thou Shall Not Use Comic Sans: 365 Graphic Design Commandments. 1st ed. Sydney, NSW: University of NSW Press.

Samara, T. (2014) Design Elements: Understanding the Rules and Knowing When to Break Them - Updated and Expanded. 2nd ed. Osceola: Quarto Publishing Group USA.

Lupton, E and Phillips, J C. (2008) Graphic Design: The New Basics. 1st ed. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Faulk, B J and Hawkins, P S and Burns, P L. (2010) British Rock Modernism, 1967-1977: The Story of Music Hall in Rock. 1st ed. Farnham: Taylor & Francis Group.

Celhay, F and Trinquecoste, J F. (2015) Package Graphic Design: Investigating the Variables that Moderate Consumer Response to Atypical Designs. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 32(6), pp.1014-1032.

TED (2019) David Carson Design and discovery. Youtube [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y7HLwtBZZI8 [Accessed 20 December 2020].

Eugenia Luchetta (2019) FUTURISM AND GRAPHIC DESIGN: THE TYPOGRAPHICAL REVOLUTION AND INCREDIBLE BOOK-OBJECTS. Pixart Printing [online]. Available from: https://www.pixartprinting.co.uk/blog/futurism-book-objects/ [Accessed 17th December 2020].

Michael Pimblett (2011) Filippo Marinetti. michaelpimblett [online]. Available from: https://michaelpimblett.wordpress.com/2011/10/11/filippo-marinetti/ [Accessed 17th December 2020].

Anon. (n.d.) Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. MoMA [online]. Available from: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/7680?artist_id=3771&page=1&sov_referrer=artist [Accessed 17thDecember 2020].

Anon. (2012) Cool Britannia: The Union Jack as a creative icon... APT marketing & pr [online]. Available from: https://aptmarketing.typepad.com/apt_blog/2012/08/patriotic-branding-the-union-jack-as-a-creative-icon.html [Accessed 18th December 2020].

Luca Beatrice (n.d.) Jamie Reid. Guidocosta Projects [online]. Available from: https://www.guidocostaprojects.com/en/events-articles/166-jamie-reid.html [Accessed 18th December 2020].

Anon. (n.d.) Jamie Reid. Artnet [online]. Available from: http://www.artnet.com/artists/jamie-reid/fuck-forever-1997-XopXZV78O06nJ9IcAbGgmw2 [Accessed 18th December 2020].

David Carson (n.d.) Newz. David Carson Design [online]. Available from: http://www.davidcarsondesign.com [Accessed 18th December 2020].

David Carson (n.d.) quiksilver. David Carson Design [online]. Available from: http://www.davidcarsondesign.com/t/clients/quiksilver/ [Accessed 18th December 2020].

Anon. (n.d.) MUSIC PRODUCTION SOFTWARE: The Definitive Guide (2019). edm prod [online]. Available from: https://www.edmprod.com/music-production-software/ [Accessed 2nd January 2021].